An Overview of Education in the Gaza Strip

Education is one of the fundamental elements that enable oppressed people under occupation to survive. Thus, over the years, the education system has served Palestinians as a “soft weapon” of resistance and resilience, passed down through generations to defend their identity, history, heritage, and existence on their land.

Since the Nakba in 1948, Palestine has faced continuous conflicts and wars with Israeli occupation forces that eventually captured their land and divided it into territories in 1967, a year known as Al-Naksa[1]. In 1993, following the Oslo Accords between Palestinians and the Israeli occupation, the Palestinian National Authority gained limited control over education in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip[2]. Later, in 1994, the Palestinian Ministry of Higher Education was established, and it developed the curriculum for Palestinian students, in addition to establishing teacher training institutes and constructing multiple schools. During the period from 1994 to 1999, education in Palestine experienced relative stability until the outbreak of Al-Aqsa Intifada in 1999/2000. After Hamas won the democratic elections in 2006 and took control of the Gaza Strip, the strip endured harsh conditions, ongoing conflict, and political instability caused by international isolation and the Israeli blockade[3]. During this tumultuous period, Gazans went through four wars—in 2008–2009, 2012, 2014, and 2021—before the outbreak of the October 7 war in 2023. Although the strip had suffered from previous devastating wars, the intensity of killing and destruction since October 7 is unprecedented. This war has been ranked among the harshest in the world in terms of the level of violence and danger to civilians[4].

Amid these devastating challenges, the educational system in Gaza, particularly higher education, has been severely affected. This paper aims to explore the challenges confronting higher education in the Gaza Strip during the ongoing war and to present potential opportunities for rebuilding and advancing higher education in a post-war scenario.

Higher Education in Gaza amid the October 7 War

Higher education in Gaza has traditionally been supported by a network of universities, colleges, and vocational institutions that have strived to provide quality education despite substantial challenges. Before the October 7 war, these institutions faced significant obstacles, including limited resources, infrastructural damage, and frequent disruptions. Despite the profound impact of a series of wars since 2008, notable educational institutions—such as the Islamic University of Gaza, Al-Azhar University, Al-Quds Open University, Palestine Technical College, Israa University, the University of Applied Sciences, the University of Palestine, and others—have demonstrated remarkable resilience and steadfastness[5].

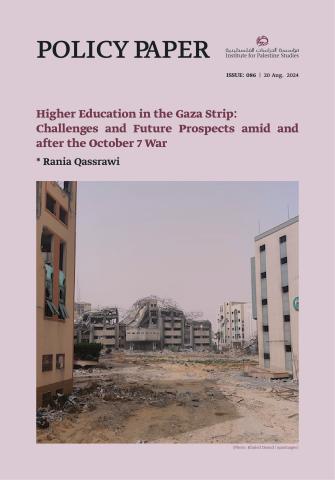

Due to the outbreak of the October 7 war, higher education institutions in Gaza have suffered severe attacks and bombings, part of a systematic effort to destroy the education sector. According to the Palestinian Ministry of Education and Higher Education, eleven out of Gaza's nineteen higher education buildings have been completely or partially damaged. Consequently, the educational process has been disrupted in most institutions, depriving nearly 88,000 students of their education[6]. The Israeli occupation officially justified targeting these institutions by claiming that they were “incubators for terrorists.” This rationale suggests that the systematic destruction was intended to dismantle Gaza's higher education system, including the extinction of educational infrastructure and the killing of hundreds of university academics, administrative staff, and students[7].

Challenges Confronting Higher Education in Gaza Today

The constant wars, ongoing genocide, and a 17-year blockade have severely impacted the higher education sector in Gaza, making it highly vulnerable as it faces significant deficits and challenges. A number of these challenges are discussed below.

Educide and Epistemicide

The Israeli occupation has pursued a systematic agenda to dismantle the education sector in Gaza since the outbreak of the October 7 war, particularly by targeting the higher education system and its institutions and staff. This has involved bombing university buildings in addition to killing and arresting Gazan university scholars, professors, academics, teaching staff, and students. On the international level, United Nations experts have expressed their concern over the attacks on schools and universities in the Gaza Strip, describing them as part of an organized plan to destroy Palestinian education. In addition, in South Africa's application to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to halt the war on Gaza, the Israeli occupation's systematic acts of educide and epistemicide—terms referring to the destruction of education, knowledge, and culture of oppressed and colonized peoples[8] —were brought to light. This application highlighted the casualties and deaths among academics, professors, and students, as well as the extensive destruction of university buildings and infrastructure, which could take decades to recover. Some of these destructive practices were detailed in the application to the ICJ as follows:

Israel has killed leading Palestinian academics, including Professor Sufian Tayeh, the President of the Islamic University—an award-winning physicist and UNESCO Chair of Astronomy, Astrophysics, and Space Sciences in Palestine—who died alongside his family in an airstrike; Dr. Ahmed Hamdi Abo Absa, Dean of the Software Engineering Department at the University of Palestine, reportedly shot dead by Israeli soldiers as he walked away, having been released from three days of enforced disappearance; and Professor Muhammad Eid Shabir, Professor of Immunology and Virology, and former President of the Islamic University of Gaza, and Professor Refaat Alareer, poet and Professor of Comparative Literature and Creative Writing at the Islamic University of Gaza, were both killed by Israel with members of their families. Professor Alareer was a co-founder of ‘We Are Not Numbers,' a Palestinian youth project seeking to tell the stories behind otherwise impersonal accounts of Palestinians—and Palestinian deaths—in the news.[9]

Infrastructure Damage

Repeated bombings and military operations have brutally damaged educational facilities in Gaza, leaving devastating and long-lasting impacts on higher education. As revealed earlier, eleven out of Gaza's nineteen higher education buildings and institutions have been completely or partially destroyed. According to Article 8 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, these acts were regarded as a war crime:

Deliberately directing attacks against buildings dedicated to educational, artistic, scientific, or charitable purposes, historical monuments, hospitals, and places where the sick and wounded gather is considered a war crime.[10].

It is noteworthy that such destruction may require decades to repair, especially since higher educational institutions in Gaza had already been suffering from shortages in educational materials, technology, laboratory equipment, and other essential facilities necessary to provide quality higher education.

Psychological Impact

Under the constant conflict and series of wars since 2008, along with a 17-year blockade, Gazans have been living stressful and frustrating lives leading to significant psychological trauma that affects their well-being and stability. According to a study conducted in 2022 by Radwan et al., the ongoing wars and blockade on Gaza (2008, 2012, 2014, 2021), coupled with the spread of COVID-19, have caused psychological traumas and disorders among university students in Gaza, including Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), a common disorder among survivors of war. It was revealed in this study that only 4.3 percent of the university students surveyed showed no symptoms of PTSD, while 88.7 percent exhibited severe symptoms[11].

During the present war, the situation has worsened as hundreds of thousands of college students have lost family members, have been evacuated and displaced from their homes, and have been starving and lacking basic daily needs. Living in these harsh conditions and experiencing such a genocidal war, students and faculty members may suffer from severe psychological disorders that negatively affect their mental well-being and impair their ability to teach and learn effectively.

Staff and Student Mobility

Due to the blockade on Gaza, the Israeli occupation has imposed strict restrictions on Gazan academics and students who wish to pursue education or professional development abroad, which has severely limited their opportunities. During this present, ongoing war, university staff and student mobility has become impossible due to the closure or strict restrictions of the crossings, especially the Rafah crossing, which is the gateway for Gazans to Egypt and the rest of the world[12]. In addition, travel fees and taxes have become prohibitively high, amounting to thousands of dollars, which has deprived many students and academic staff in Gaza's higher education institutions of the opportunity to travel abroad.

Financial Dilemmas

The people of Gaza have been under a long blockade, which has diminished the financial capacities of Gazan families and increased the unemployment rate. The main financial sources for higher education institutions are students' tuition fees and the annual allocations from the Ministry of Higher Education. During the genocidal war after October 7, these financial resources were directly impacted since students were unable to afford tuition fees, resulting in universities being unable to pay salaries to staff and employees, which has led to significant deficits in this sector.

High School Students and Tawjihi Exams

Higher education relies heavily on preceding education stages, particularly secondary (high school) education. Due to the ongoing war on Gaza, 39,000 students have been deprived of education, as schools and other educational infrastructure have been destroyed, according to the Palestinian Ministry of Education and Higher Education (2024)[13]. Consequently, higher education institutions have been significantly affected by the loss of the incoming freshmen class that was supposed to enroll in colleges and universities this year. This negative impact will persist for four years at least as higher education institutions are missing the 2024 cohort.

Scenarios for the Future of Higher Education in the Post-war Period in Gaza

Envisioning the future of higher education in post-war Gaza involves addressing immediate recovery needs and building a sustainable and resilient educational system. Some measures and steps are proposed below.

Rebuilding Sustainable Infrastructure

As an initial step for reforming higher education in Gaza, priority should be given to the reconstruction of damaged facilities and the development of new, resilient, and sustainable infrastructure that can withstand future crises[14]. This effort should involve modern architectural designs that integrate physical durability and the ability to support advanced educational technologies. During the reconstruction period, university students could pursue their education in temporary local buildings based on their residency to continue with minimal disruption until the higher education institutions and facilities in Gaza are fully restored, at which time students would be able to join the university campuses.

Enhancing the Education System at All Levels

Improving the education system across all stages—preschool, primary, and secondary—must be an urgent priority. Strengthening these foundational levels is crucial for preparing students to complete high school and pursue higher education successfully[15]. This step includes ensuring that educational curricula are updated to meet current global standards by providing adequate teacher training and integrating technology into the learning process from an early age.

Adopting Pioneering Educational Models

In the post-war period, designing educational models that offer flexible and accessible higher education to Gazan students will be vital. These models should embrace technology and incorporate online and blended learning to provide a wide range of educational opportunities even in times of crisis. Developing these models requires the professional development of academic staff to handle new teaching methods and technologies effectively. In addition, there should be a focus on vocational training that aligns with local economic needs and the job market.

Encouraging Twinning Programs

Twinning programs, which involve partnerships between educational institutions to share knowledge, resources, and best practices through collaborative efforts[16], could support Gaza universities and higher education in the post-war phase in multiple ways. For instance, these programs would provide an opportunity for capacity building, knowledge exchange, resource sharing, cultural exchange, and sustainability.

Establishing a Virtual Database Cloud

Due to the threat of data loss during the war on Gaza, a virtual database cloud would enable the centralization of essential records for universities, such as educational materials, staff and student academic records, and so forth. The virtual database cloud would securely store such data and be easily accessible. Thus, educational institutions could continue to operate even if the physical infrastructure were damaged[17].

Providing Psychological Support

Implementing healthy psychological support systems for both students and faculty will be essential in the post-war period to address trauma and promote mental well-being. The introduction of counseling services, peer support groups, and community engagement programs could offer vital support in helping individuals cope with the post-war environment. Additionally, comprehensive mental health support programs designed for students and faculty should be developed. These initiatives could include regular mental health screenings, workshops on stress management, and access to professional mental health services.

Achieving Local Solidarity and Collaboration

Strengthening local solidarity between higher education institutions in the West Bank and those in Gaza is key to creating a unified and resilient educational network. Initiatives like the Palestinian Ministry of Education and Higher Education's 2024 programs, which include the “Rebuilding Hope Initiative” by Birzeit University[18], exemplify a form of solidarity between colleges and universities in the West Bank and Gaza by instigating special programs for Gazan students. These initiatives could allow students to continue their education online, supporting students' academic progress.

Launching International Campaigns for Support and Funding

Starting international campaigns to gather support for Gaza's higher education sector will be necessary in the post-war phase. These campaigns could raise awareness about the challenges faced by students and faculty members seeking moral and financial assistance from global institutions. Hence, securing international aid for the reconstruction of educational infrastructure and the provision of essential educational resources will be a cornerstone of the rebuilding process. Partnerships with international universities, development agencies, and donors could provide the necessary funding and expertise to rebuild Gaza's higher education system more vigorously than before. This support could also extend to offering scholarships, staff and student exchange programs, and capacity-building initiatives that benefit both students and academics.

Conducting Policy Reforms

Promoting effective governance and policy reforms is critical in the post-war period to improve the resilience and quality of the higher education system in Gaza. These reforms could involve revising educational policies to incorporate disaster risk management, guaranteeing that institutions are better prepared for future crises. Additionally, reforms should focus on enhancing academic freedom, ensuring the equitable distribution of resources, and promoting inclusive education for all students regardless of their social or political backgrounds[19].

Promoting Community Engagement

Fostering community support and involvement in educational reforms is crucial for building a supportive academic environment in the post-war phase[20]. Engaging local communities in the rebuilding and development process could enhance the sense of ownership and responsibility toward educational institutions. Community initiatives could complement formal educational efforts and help bridge gaps in resources and support.

Conclusion

Undoubtedly, the higher education sector in the Gaza Strip faces immense challenges due to the intentional and systematic cruel practices that aim to destroy the education sector. However, education in the Palestinian context will remain a form of resilience and resistance cherished and embraced as a hope for a brighter future. Therefore, local and international efforts must be focused on doing everything possible to stop the ongoing genocidal war on the Gaza Strip. In addition, serious measures and steps must be taken, such as addressing immediate recovery needs, fostering local and international collaborations, and incorporating pioneering educational models, to rebuild and renovate the education sector in general and the higher education system in particular.

[1] Susan Nicolai, Fragmented Foundations: Education and Chronic Crisis in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (Paris and London: UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning and Save the Children UK, 2007).

[2] Mahmoud Nofal, Fawaz Turki, Haidar Abdel Shafi, Inea Bushnaq, Yazid Sayigh, Shafiq al-Hout, Salma Khadra Jayyusi & Musa Budeiri, “Reflections on Al-Nakba”, Journal of Palestine Studies, vol. 28, no 1 (Autumn, 1998), pp. 5 - 35.

[3] “War on Gaza: Twenty-first century's deadliest 100 days?”, ESCWA, February 2024.

[4] “WFP in Gaza: ‘We need a long ceasefire that leads to peace so we can operate'”, by OCHA, Relief Web, 8/8/2024.

[5] "مؤسسات التعليم العالي؛ الجامعات والكليات الفلسطينية"، رام الله: وزارة التربية والتعليم العالي، 2024.

[6] "'اتحاد مجالس البحث العلمي العربية‘ يدين عدوان الاحتلال واستهداف المؤسسات العلمية"، وكالة الأنباء والمعلومات الفلسطينية "وفا"، 22/12/2023.

[7] "مركز 'شمس‘ تدمير الاحتلال للمدارس والجامعات في قطاع غزة، سياسة تجهيل وتدمير للمسيرة التعليمية والثقافية الفلسطينية"، رام الله: مركز إعلام حقوق الإنسان والديمقراطية شمس، 7/11/2023.

[8] Boaventura De Sousa Santos, Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide (London: Routledge, 2014).

[9] “Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide in the Gaza Strip (South Africa v. Israel)”, ICJ, 28/12/2023.

[10] “Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court”, Hague, Netherlands: International Criminal Court, 2021.

[11] Abdal-Karim Said Radwan, Maysoon Khalil Abu-El-Noor, Rania El-Kurdy, Yousef Aljeesh and Nasser Ibrahim Abu-El-Noor, “Post-traumatic Stress Disorder among Palestinian University Students following the May 2021 War”, Research Square, 30/3/2022.

[12] “UNRWA Situation Report # 76 on the Situation in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem”, UNRWA, 12/2/2024.

[13] Rami Samarah, “Gaza's High School Students Deprived of Final Exams amid Ongoing Israeli Genocide”, Palestine News & Info. Agency WAFA, 22/6/2024.

[14] Aaron Opdyke and Amy Javernick-Will, “Resilient and Sustainable Infrastructure Systems: The Role of Coordination, Stakeholder Participation, and Training in Post-disaster Reconstruction”, ResearchGate, July 2014.

[15] “Education for All” UN.

[16] “Twinning Partnerships for Improvement: Building Quality Health Services for COVID-19 Recovery and Beyond: advocacy brief”, World Health Organization, 13/5/2024.

[17] Polyxeni Spanaki & Nicolas Sklavos, “Cloud Computing: Security Issues and Establishing a Virtual Cloud Environment via Vagrant to Secure Cloud Hosts”, Computer and Network Security Essentials (Berlin: Springer, 2018), pp. 539 – 553.

[18] Rebuilding Hope: Birzeit University's initiative to support and resume higher education in Gaza.

[19] Nazmi Al Masri, “Inclusive Education in Occupied Palestinian Territories”, Disability Under Siege Network, Literature and Practice Review – March 2021.

[20] “Community Engagement during Times of Crisis: COVID-19 and beyond”, The Policing Project at New York University School of Law, 20/5/2020.